RPG-Progression

What do we understand by progression in RPGs?

Game progression refers to momentum earned via in game abstraction: Leveling up a character, unlocking a new skill, beating level one and going to level two and so on. What’s interesting about the two is that you can’t really track player progression on its own, but it can be measured through game progression.

Obviously someone who is really good at the game will be able to beat more levels and earn more achievements compared to someone who isn’t. Both forms of progression have the same goal: To prevent the player from feeling like their time is being wasted.

Why is important a good progression?

A good progression model motivates the player to keep playing; no matter if they’re winning or losing. Nothing stops someone more from playing a game when it feels like they’re not making any progress, or they’re losing it. Even if the progress can be measured in centimeters, as long as they’re moving forward, the player will still be motivated

This progression can be divided into player, playable character and game:

Progression Types

Player

“Player” progression refers to the person playing the game improving their skill and knowledge of the design. Many action-based titles are designed around the player getting better at the game to have any chance of winning — a big example being the Souls series.

Character

“Character” or “Abstracted” progression refers to the in-game avatar becoming stronger outside of the player’s skill. RPGs are the best example of this, and the whole abstract concept of leveling up.

Game

Moving through the various levels or areas of the game until you reach the credits.

Depending on the design of your title, you may have any combination of the three as the focal point. The important part is understanding what progression means to your title and to the people playing it.

The three types of progression that I have discussed before focus on the element that progresses, but how does this element progress? There can be two types of progress, positive, the most used in digital RPGs, or negative, less seen in video games but quite used in tabletop role-playing games.

Positive progression always improves stats from low to high. Although there are attacks that can lower you some stat, if this decrease is only during combat, it is not considered negative progression.

On the other hand, negative progression is usually internal or external factors of the character that cause your stats to decrease. There can be many different reasons, for example, you reach a high age, you have died many times, or you have been cursed for life. Example of games with negative progression:

Might and Magic VIII (2000)

This game has an age penalty system. Your characters have an age variable that increases over time. When you reach a certain age, the stats are reduced and even, after 80 years of age, in the middle of a fight, you can die.

Wizardry VI (1990)

In this game when a character in your group dies, you can revive him, but with less and less life. When it reaches 0 health after being revived several times, it can no longer be used.

But, let’s go further, before digital RPG games were created. Let’s talk about the first official character progression system.

Basic Role-Playing

Basic Role-Playing it’s a rule book of a tabletop role-playing game which originated in the RuneQuest fantasy role-playing game, in 1980. BRP is similar to other generic systems such as GURPS, Hero System or Savage Worlds in that it uses a simple resolution method which can be broadly applied. BRP uses a core set of seven characteristics: Size, Strength, Dexterity, Constitution, Intelligence, Power, and Appearance or Charisma. From those, a character derives scores in various skills, expressed as percentages. These skill scores are the basis of play. When attempting an action, the player rolls percentile dice trying to get a result equal to or lower than the character’s current skill score.

The last major element of many BRP games is that there is no difference between the player character race systems and that of the monster or opponents. By varying ability scores, the same system is used for a human hero as a troll villain. This approach allows for players to play a wide variety of non-human species.

Grind

What is this?

“Grinding” or “Grind” can mean different elements depending on the genre and player, we’re going to define it as this:

Grind: The period of time in a game when the player’s ability to progress is reduced to a few set options, and everything else will not move them forward.

One of the key signs that your game becomes a grind is when there are things the player could be doing, but doing them would be a waste of time at this point. A famous example is from the MMO genre, and if the player runs out of quests at their level range to do, doing lower level quests will not earn them anywhere near the experience needed to keep going.

How to eliminate grind?

To eliminate or mitigate grind, the first step for any game regardless of design is to look at the trouble areas of your game. At what point do you see people quitting, and is there a period in your game that is taking the longest to get through?

From there, it comes down to adding in more viable options for progressing. One of the simplest, yet effective systems is the concept of “milling.” Milling is a term used in CCG and F2P-styled games, and is the act of taking a resource or item you don’t want, and converting it to something you do.

Knowing how to win, but not being able to do it yet, is one of the worst aspects of padding out a game

Fairy dust in Hearthstone is an example of this practice. We can also see this in Darkest Dungeon with the ability to trade heirlooms.

The more ways for a player to make progress will decrease the chance of the game becoming a grind. Some titles will let any action the player does contribute towards experience or leveling up.

Bad example of grinding

The Inazuma Eleven saga has a mechanic of random matches or friendly matches throughout the game. As you go down the street, from time to time, a team appears that challenges you to a match. These matches are the equivalent in a classic RPG to a combat. These fights cannot be avoided in any way, unless you have a special item, difficult to obtain. At first it´s fun, but over time you get tired of repeating the same thing all the time without receiving anything positive in return. This is a form of grinding, in Inazuma Eleven Go it is fixed:

Good example of grinding

In Inazuma Eleven Go they have some random encounters, but only once per NPC. Then you will find the NPCs in the same place to be able to challenge them if you want. You don’t force the player to have to face each other all the time, you let him decide whether to grind or not.

RPG Level-Based Progression

The general idea is that the more is your level, the more experience you need to advance to the next one. This is true, but it is just a small part of the design. In fact, you must keep in mind the effect of any gameplay element on the player, and you must be sure that what you do produces the emotion you want to convey.

Why using this system?

Levels and experience points are a popular mechanic with both players and designers for some of the following reasons:

Sense of Achievement

Gaining a level gives the player a sense of achievement and it’s an acknowledgement of the player’s efforts. When the level number increases it’s a way of giving the player a pat on the back and saying “Good job!”. The number increasing is a small reward all on it’s own but RPG’s usually give out additional rewards by increasing the players stats and sometimes unlocking special abilities.

The value in gaining a level is related to how difficult it is to achieve. In order for a level to have value, the player needs to struggle and overcome adversity to reach it. Higher levels require more XP and take longer to reach because the time invested is proportional to the reward. The distance between levels gives them meaning.

The Hero’s Journey

JRPG characters are literally on a hero’s journey. Their level indicates how far they’ve come from the starting point and hint how far is left to go.

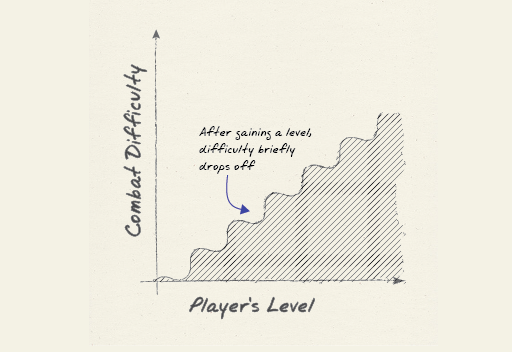

Levels describe the characters growth as they overcome obstacles in the game. Each level bumps the character’s stats, so as the character levels up they become stronger and more powerful in the game world. The flow of the game represents this, the enemies the player is currently battling will suddenly be a little easier, but very quickly the player will discover more powerful enemies and will be battling up hill again. If combat ever gets too easy, it becomes boring.

Difficulty follows a step function, things become briefly easier only to become even harder than before.

Dripfeed Complex Mechanics

Most JRPGs have quite complicated battle mechanics with status effects, various types of spell, elements, chain attacks and so on. The battle systems can be so complicated that it’s too much to try and show the player all at once. Instead as the player slowly levels up, mechanics are introduced in understandable chunks. This dripfeed helps make the game more accessible and the shallows out the learning curve.

At level 1 only the most basic mechanics are available making combat straight forward for a new player. The choices are very restricted, so the player can quickly try them all out. Gaining levels unlocks new abilities and spells which the player can immediately try out and get comfortable with before the next mechanic is introduced.

This dripfeed also applies to enemies. Early in the game enemies exhibit simple behaviors and few abilities but as the characters level up and progress to new areas, they meet new monsters with special attacks and more advanced tactics. For the player to encounter these more advanced enemies, they must first defeat the simpler enemies by mastering the basic combat techniques.

Control the Flow of Content

Levels help drip feed mechanics but they also help control how the player navigates the world.

Is there a cave where the monsters are far too hard? Maybe the player can’t tackle it yet, but they’ll remember the cave, it will become a goal, something to return to with stronger characters.

Levels also control how quickly a character can dispatch monsters, which controls how fast and easily a character can travel from place to place and how long a play-through of the game will take.

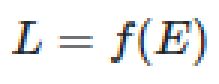

At the basis of level-based progression, there are experience points. Mathematically speaking, level progression is a function mapping a certain amount of experience to a certain level:

Experience curves

A function that, given a level, tell us how much experience we need for this:

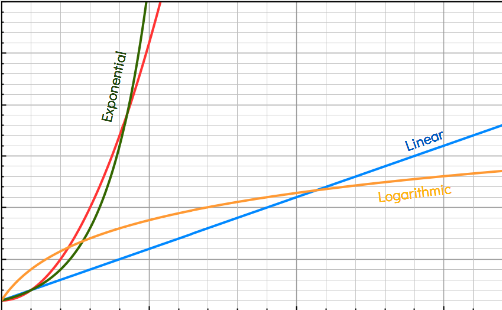

Linear: Every level needs the same extra amount of experience: 10 for Level 2, 20 for Level 3, 30 for Level 4, …

Exponential: We always need more experience than the previous level, and therefore we level-up slower at the end game.

Logarithmic: At every level, we need less experience to level-up and, consequently, the more we play, the faster we level-up.

Real Examples

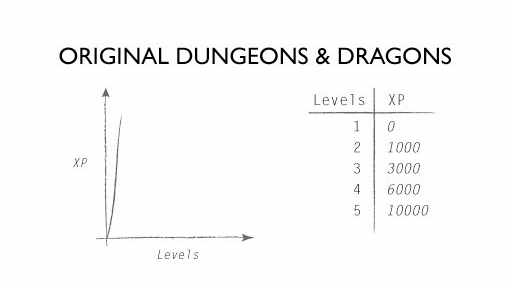

Original D&D

Dungeons and Dragons is the game many early JRPGs used for their inspiration, so it seems only fair to include it’s level function.

function nextLevel(level)

return 500 * (level ^ 2) - (500 * level)

end

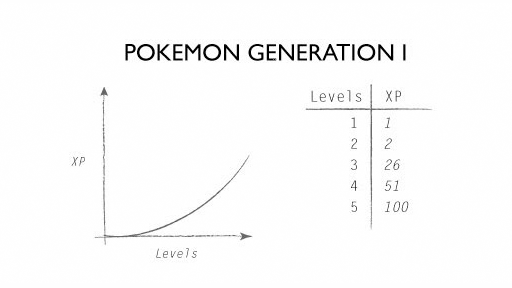

Generation 1 Pokemon

Pokemon actually has two leveling systems, this is the faster of the two.

function nextLevel(level)

return round((4 * (level ^ 3)) / 5)

end

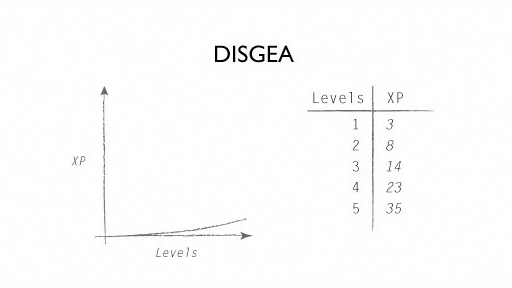

Disgaea

Disgea applies this formula to the first 99 levels after that it changes things up.

function nextLevel(level)

return round( 0.04 * (level ^ 3) + 0.8 * (level ^ 2) + 2 * level)

end

Balancing the game

Why is game balance important in a single-player game?

Ideally, each type of character build has its own strengths and weaknesses throughout the game’s content, but ultimately ALL character builds should feel viable in different ways. No player wants to spend 40 hours working toward a dead-end build.

RPGs, are about choice and consequence. That doesn’t just apply to the narrative elements, but also gameplay: character creation, character building, and tactical application of skills and abilities in the wild. If we do our jobs well, players will feel the sting of character weaknesses and the satisfaction of character strengths over the course of the game. Challenge is a tricky thing to balance for a wide range of players, but ideally it builds by giving players short periods of stress and mild frustration caused by a mental obstacle. Players examine the obstacle, consider their options, make choices, and eventually overcome it, transforming stress into a sense of exhilaration at their own ingenuity.

What Sort of Decisions Do We Want the Player to Make?

Strength vs. Charisma, fighter vs. rogue, sword vs. axe—but also, the criteria that drive those decisions. These criteria could be as broad as deciding between a character class that does a lot of damage in combat vs. a class that is great at navigating conversations. Or, they could be as narrow as emphasizing attack speed over damage done on a Critical Hit.

There are two levels at which players generally make these sorts of decisions. The first is aesthetic and conceptual: “Wizards are cool.” “Clubs are boring.” “Being strong owns.”

The second is mechanical/rational: “High damage is important.” “Gotta have a healer.” “Debuff effects can make a huge difference in fights.”

Different players balance these desires differently, but ideally an aesthetic choice will always map to a viable build, and a viable build will map to something players will find cool for their character. When this doesn’t happen, it can result in a lot of annoyance from players. They are either forced to play something they conceptually like that is mechanically bad or they have to veer away from their character concept to be mechanically viable.

Knowing your audience

Yes, RPG gamers are a diverse bunch, and what might be fun for one gamer can be agony for another. However, that doesn’t mean you can’t make a well-balanced, crowd pleasing game. And one of the best ways to do this is to start by understanding the kinds of gamers who play RPGs. Categorized by type, they are:

- The Casual Gamer: The casual crowd is more interested in progression then challenge. Present them with a battle they cannot defeat in two or three tries, and they’ll likely swear off your game forever.

- The Hardcore Junkie: There are gamers who want to be challenged at every juncture. They value the sense of accomplishment associated with overcoming heroic tasks more than story progression. Some, like those who play Dark Souls, are just gluttons for punishment.

- The Math Nerd: They’ll crunch numbers, draw graphs and come up with advanced predictive models, all so they can fully optimize their characters. These gamers don’t mind grinding experience, as long as it will help them to improve their character’s stats.

- The rest of us are gamers who want to be periodically challenged at critical turning points, but prefer to sail through trash mobs. Gamers of this variety enjoy leveling and building powerful characters, but would rather be slightly less powerful than spend the majority of their time grinding out levels.

Determining the percentage of gamers that fall into each category would be difficult, especially in the current gaming climate.

Bibliography

https://www.worldanvil.com/w/cd10/a/design-philosophy-progression-systems

https://www.davideaversa.it/blog/gamedesign-math-rpg-level-based-progression/

https://medium.com/@GWBycer/the-limitations-of-leveling-systems-in-game-design-f06a2a14c026

http://howtomakeanrpg.com/a/how-to-make-an-rpg-levels.html

https://my.eng.utah.edu/~zagal/Papers/Zagal_Altizer_RPG_Elements_Progression.pdf

https://www.slideshare.net/IvanMilev2/examples-of-different-leveling-and-skill-points-systems

https://en.uesp.net/wiki/Skyrim:Leveling

https://pathofexile.gamepedia.com/Path_of_Exile_Wiki

https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/2843/applying_risk_analysis_to_.php

https://diablo.fandom.com/wiki/Character_Level#Diablo_II

https://kotaku.com/how-to-balance-an-rpg-1625516832